Dr. Lanny Smith and Doctors for Global Health

For Dr. Lanny Smith, the pivotal moment came when he traveled to Nicaragua in 1985 with a peacemaking group and volunteered with Habitat for Humanity. In what he describes as a "life-changing experience," Dr. Smith lived with a Nicaraguan family and experienced firsthand the living conditions of poor Nicaraguans, as well as the political climate. "We heard gunfire every day," he said. He interviewed people who had been brutalized by US-funded Contra rebels and had seen their clinics and schools attacked. These experiences shaped his perspective on human rights.

As a medical student, he continued to visit Nicaragua and, while in residency at Boston City Hospital, Dr. Smith became very active in various Central American solidarity groups. After obtaining a scholarship to study public health, he went to El Salvador in 1992 on what he thought would be a nine-month trip to work with the French relief organization Médecins du Monde (MDM). His focus was on helping Salvadorans rebuild their lives after twelve years of civil war and on training health promoters. He chose to work in an area where the local people had themselves organized to work in education and agriculture but not in healthcare. After the peace accords and disarmament took place, many international groups decided to withdraw from El Salvador, but Dr. Smith convinced MDM to stay.

Founding DGH

In 1995, amidst ongoing violence and injustice, Dr. Smith and other volunteers working in the province of Morazan formed Doctors for Global Health (DGH). The philosophy underpinning DGH stressed the promotion of health and human rights around the globe. The establishment of the group also helped them in obtaining funding on their own and allowed for a structure by which its large group of volunteers could come and work in El Salvador.

DGH developed a vision referred to as Liberation Medicine. Dr. Smith defines it as "the conscious and conscientious use of health to promote social justice and human dignity." The organization considers itself a social movement and is a founding member of the Global Peoples Health Movement.

DGH only works in areas where it has received a written invitation by the local population, who determine their own priorities. DGH uses its resources to address these priorities while lending its own expertise. Volunteers consider their work as accompaniment, which means walking or working with people as they try to change their lives.

In addition to locating funding for materials and services, DGH recruits volunteers and provides training to local people who then function as health promoters within their home sites. It emphasizes empowering communities to manage their health through education and public health services. DGH operates in communities in Latin America, Uganda, and the United States. Two of its most inspiring stories are in Santa Marta, El Salvador and Altamirano, Mexico.

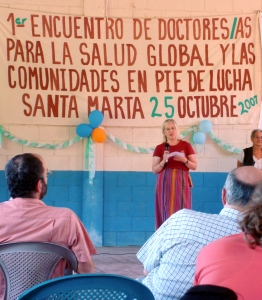

Rebuilding Santa Marta

Santa Marta, a community of 3,000 near the Honduran border, was destroyed during the civil war, and many of its population fled to refugee camps in Honduras. They returned in 1987 after six years in the camps and rebuilt their community from the ashes of destruction.

In 2001, Denise Zwahlen, a physician's assistant with experience in community health, was the first DGH volunteer to arrive there. At that time, a rehabilitation clinic staffed by local health promoters existed and consisted of a one-room mud house with a dirt floor and a tin roof. With financial assistance from DGH and another nongovernmental organization, that clinic has expanded to a two-room cement structure that provides a wider range of services to patients, including physical therapy and children's health issues. DGH also arranged to provide funds for the health promoters and volunteers who work there. The clinic now collaborates with a clinic run by the Salvadoran Ministry of Health.

The infections and diseases that Ms. Zwahlen sees most often in Santa Marta are those related to poor living conditions, such as gastrointestinal diseases stemming from parasites; asthma in children, which comes from breathing in fumes from burning garbage, since there is no adequate sanitation; acute respiratory illnesses; and malnutrition-related conditions.

"Cervical cancer is the leading cause of death among women, when it is a highly preventable disease," Ms. Zwahlen said. "Diseases are not addressed quickly enough because of the poverty, contamination, lack of knowledge and lack of services." She also believes that a big challenge is chronic illness, such a hypertension and diabetes, and lack of access to medications.

To counteract the lack of knowledge, education has been a priority among the people of Santa Marta. One of DGH's biggest involvements has been with the local youth. DGH helped to raise funds for a local high school and provide volunteers who teach or assist the teachers with the curriculum. Previously, few people in the community went to high school; now, young people have the chance to complete their education, and 35 students have gone on to advanced studies at the university in San Salvador.

Another project that DGH was instrumental in funding is a youth group promoting AIDS education, the Comite Contra SIDA (CoCoSI). CoCoSI is a well-organized and active group, consisting of young people aged 15 to 24, whose focus is on AIDS-HIV education and outreach. CoCoSI provides services for AIDS sufferers, support, advocacy, and teaching about the issues that contribute to being at risk. The group now also visits other rural communities in El Salvador and Honduras, detention centers and jails, and it works in schools teaching reproductive health. CoCoSI has come to be recognized for its work. The Ministry of Health partly credits them with the lowest rate of teen pregnancy in Santa Marta. Santa Marta's young people have also participated in the Healthy Agriculture Project, designed to raise awareness of the health effects of pesticide usage.

According to Ms. Zwahlen, one of the benefits of her volunteer work is "not only the impact you have on the community, but the impact the community and the work you do there has on the volunteers." DGH volunteers have opened their eyes and their minds to what has happened in El Salvador and realized the impact of US policies on the nation. Many have reinforced their commitment to practice Liberation Medicine or their desire to work in international health.

Reaching Chiapas

In 1998, Dr. Linnea Capps became the first long-term DGH volunteer to work in Mexico's southernmost state, Chiapas, site of the 1994 Zapatista uprising against the Mexican government. She spent a year there and still travels there annually, staying for a couple of months.

DGH was invited to Chiapas a few years after the uprising by people working in the native Mayan communities. Dr. Capps began working at a small hospital, Hospital San Carlos, run by an order of Catholic nuns in the town of Altamirano. Her arrival came after a recent massacre in an Indian village at the end of 1997, and she recalled "that whole year, it was very difficult to go out and meet anybody in the communities and work directly with village health workers because there was so much military surveillance of areas that were supposedly Zapatista sympathizers." She worked to get to know the communities her first year. Since then, DGH volunteers have worked in the hospital and helped develop community health programs.

DGH's goal focuses on long-term work with communities to help them improve their health. A major part of this work in Chiapas is health promoter training. Volunteers working in 10 communities are trained in public health issues -- among them, preventive medicine, vaccination, and sanitation. Health care promoters are also trained on how to recognize and treat simple illnesses and how to determine when the patient needs more advanced care.

Typical conditions found among the inhabitants include tuberculosis, which is prevalent in the area, diabetes, diarrheal illnesses among children, malaria, hookworms caused by people not wearing shoes and leading to anemia, and Chagas disease, brought on by a parasite and affecting people living in substandard housing. Chagas disease is the most common cause of heart disease in the area.

An obstacle facing healthcare practitioners is misconceptions of chronic illness. For instance, in treating diabetes, Dr. Capps said, "It's very hard to explain that it can't be cured. People tend to drop out of care because they don't understand the nature of chronic, controllable, but not curable illness."

Another obstacle is funding for the hospital, which runs on a shoestring budget. It depends on funding from various sources, and treatment for chronic illnesses or diagnostic tests are many times not available.

Despite these hurdles, the hospital and DGH have succeeded in achieving trust among people who have traditionally distrusted outsiders and are now more receptive to efforts to develop community health plans. Patients from the local communities often bypass government hospitals to come to Hospital San Carlos.

A Success Story

One of the individual success stories is provided by a local health promoter, Jacinta, who came from an isolated community and a male-dominated culture. Jacinta learned to speak some Spanish and organized a group of women from different communities to start a collective meant to improve their lives economically. Dr Capps says, "It's just an inspiration to see what she's accomplished and what kind of person she's become from a background that gave her no advantages at all."

While cautious about the time that it will take DGH to help make changes, Dr. Capps asserts, "We are not a huge organization. We don't have a lot of money or a lot of access to resources....We make long-term commitments."

Besides commitment, DGH is strong on human resources, as its global membership of 6,000 illustrates. The organization welcomes all people who are concerned about health and social justice in the world to participate in its mission of helping people build healthier and more equitable lives.

About the Author

Shyla Nambiar is a freelance writer based in Atlanta, Georgia.

About Angels in Medicine

Angels in Medicine is a volunteer site dedicated to the humanitarians, heroes, angels, and bodhisattvas of medicine. The site features physicians, nurses, physician assistants and other healthcare workers and volunteers who reach people without the resources or opportunities for quality care, such as teens, the poor, the incarcerated, the elderly, or those living in poor or war-torn regions. Read their stories at www.medangel.org.