A unique foe – controlling the tsetse fly

A story by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi)

Photos by Brent Stirton/Getty Images for DNDi

(Read the Introduction to this series here.)

The mangroves provide a livelihood for the hundreds of thousands of people who live in or alongside these wetlands. The channels that crisscross the brackish swamps are essential transport waterways, connecting remote communities that depend on fishing or cultivating the many riches of the mangrove.

But these same channels also act as ‘highways’ for the tstetse fly, according to Dr Bucheton, whose organization, the IRD, has supported the Guinean government’s ‘vector control’ programmes to control the tsetse fly.

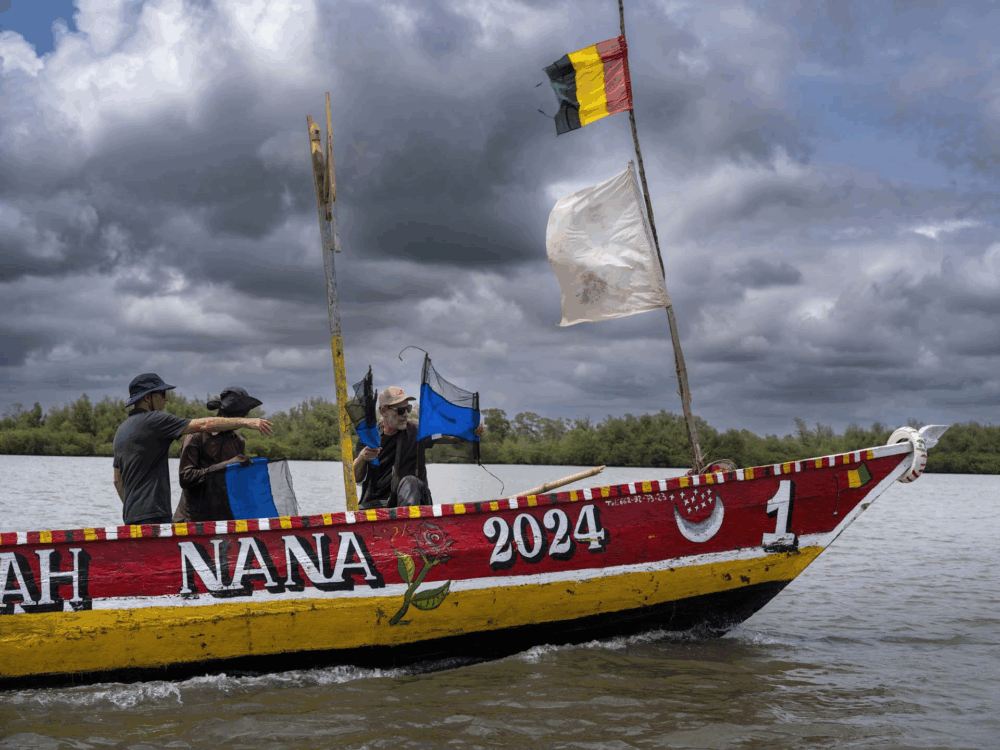

Both male and female tsetse flies can transmit the disease. Many people are bitten and infected while traveling the mangroves in canoes or by foot. To control the flies, the Programme uses ‘tiny targets,’ or the ‘blue flags’ as they are known by the local populations. The flies are attracted to the blue (scientists don’t exactly know why).

While flying close to the water along the mangrove, they land on the flag where a dose of insecticide kills them in a matter of minutes. The National Programme sets up traps strategically, close to where humans farm, fish, and access the vast mangroves by boat. The idea is to break the contact between the vector, the fly, and the human host, so the teams focus on putting the flags in places where they know the flies are infections – where there have been recent cases of the disease.

They are helped along by the tsetse fly’s unique life cycle. Unlike other insects that release thousands of eggs, tsetse flies only produce a handful of larvae in their three-month lifespan. Females will fertilize only one egg at a time and feed the developing larvae milk in the uterus – a phenomenon that Dr Bucheton likens to breastfeeding.

Unlike other insects, the flies don’t lay their eggs in water where they can be eaten by predators – the mother gives birth to single pupa, which then burrows into the ground while it develops.

Because it makes so few larvae, it is possible to rid an infected tsetse fly population of the sleeping sickness parasite in a given area. But the ecosystem of the mangrove presents some particular challenges.

‘If we put them too low, when there is a higher tide there is a risk the trap can be destroyed or come loose because of the rising water. So, they set the traps when they know the tides will be at their highest,’ says Dr Bucheton. ‘But we still lose many traps – it’s a huge problem in the mangrove. Traps need to be constantly replaced – they get soaked in water; the wind destroys them.’

The village of Kéréba is a perfect example of the Programme’s success. Although the skyline of Conakry is visible from this tiny village, it is only reachable by boat. Kéréba is a temporary settlement where villagers ‘mine’ salt by digging trenches in the mangrove to collect tidal water. They then extract the salt from it through a laborious process of burning mangrove wood.

The Programme has been traveling the mangrove by boat to set up tiny targets for some time now in and around the community – and the work is paying off. Kéréba has had zero cases of sleeping sickness for two years now.

Tsetse fly control works.

Coming soon! Step 2: Building trust

Related Articles

Bölët Mouna: Inside Guinea’s Quest to Eliminate Sleeping Sickness (Step 4)

Guinea has achieved a historic milestone by eliminating sleeping sickness as a public health problem, becoming the first country to conquer this deadly neglected tropical disease with the support of DNDi. In Step 4, read about going the last mile.

Bölët Mouna: Inside Guinea’s Quest to Eliminate Sleeping Sickness (Step 3)

Guinea has achieved a historic milestone by eliminating sleeping sickness as a public health problem, becoming the first country to conquer this deadly neglected tropical disease with the support of DNDi. In Step 3, read how going door to door helped the process.

Bölët Mouna: Inside Guinea’s Quest to Eliminate Sleeping Sickness (Step 2)

Guinea has achieved a historic milestone by eliminating sleeping sickness as a public health problem, becoming the first country to conquer this deadly neglected tropical disease with the support of DNDi. In Step 2, read how community trust was built.