A group of nurses in East Baltimore is piloting a bold plan to bring basic primary care to everybody no matter their age, income or insurance. Can this idea from abroad take root in the United States?

First published June 6, 2024 by Tradeoffs.

Raquel Richardson arrived at work in the Johnston Square Apartments in East Baltimore this February expecting to have just another Tuesday. The 31-year-old typically spends her days solving residents’ problems, answering questions at reception and making maintenance rounds.

That day, however, she noticed a team offering free blood pressure checks in the lobby — and decided to sit for one too. Tiffany Riser, a nurse practitioner, was so alarmed by Richardson’s high reading that she checked it twice. The young woman, the nurse confirmed, was at immediate risk for a stroke.

Riser only caught this threat to Richardson’s health because she was offering convenient, preventive care as part of a new program called Neighborhood Nursing. The idea is to meet people where they are and offer them free health checks, whether they realize they need them or not. If Richardson had waited until symptoms arose, Riser says, the results could have been disastrous.

Instead, Richardson quickly got on a new blood pressure medication and received additional information from Riser about how to reduce hidden salt in her diet. Months later, her pressure remains at a healthy level.

Bringing care out of the clinic and into the community

Neighborhood Nursing’s teams of nurses and community health workers have started making weekly visits like these to the lobbies of three apartment buildings in Johnston Square, one of Baltimore’s most marginalized neighborhoods. By next year, the team aims to visit more than 4,000 people in the Baltimore metropolitan area at least once a year.

“We’re trying to turn primary care on its head and deliver it in a completely different way,” says Sarah Szanton, dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing and leader of the project, which is a collaboration with the Coppin State, Morgan State and University of Maryland nursing schools. “What’s revolutionary,” Szanton says, “is that it’s for everybody” — whether they are sick or healthy, rich or poor, young or old, and no matter if they have private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, or no insurance at all.

The visits are free to the patient and prioritize each person’s unique goals, from managing chronic back pain to finding safer housing. They can take place in people’s homes, senior centers, libraries or even laundromats.

The idea is modeled after a similar program first tried in Costa Rica about 30 years ago, when that country was grappling with the same core problem that the U.S. is experiencing today: Patients are struggling to access preventive primary care, especially in poor and rural areas. Hospitals are overflowing and basic needs from hunger to high blood pressure are spiraling into bigger, costlier problems.

Szanton believes the U.S. — which lags behind other high-income countries on many measures like infant mortality and obesity — is sorely lacking bold solutions.

Compared to other countries, the U.S. spends far more resources on treating illnesses than on preventing them. America only puts about 5 cents out of every dollar spent on health care toward primary care — and spends less than peer nations on social supports like food and housing.

“It’s like if 10% of our houses were on fire, we would say we don’t have enough firefighters,” Szanton says. “But really what you need to do is prevent fires, which we’ve never done for medical care in this country.”

A primary care approach imported from a land 2,000 miles south

Costa Rica’s national approach to primary care is very different. “It’s pretty much night and day,” says Asaf Bitton, a primary care doctor who has studied Costa Rica’s model and directs Ariadne Labs, a health innovation center at Harvard School of Public Health.

The Central American nation of 5 million people has pioneered a nationwide version of Neighborhood Nursing. Teams of health workers visit residents’ homes at least once a year, whether the patients live in cities, on banana farms or in remote villages reachable only by boat. After three decades of this approach, the results are remarkable.

Deaths from communicable diseases like tuberculosis and hepatitis have fallen by 94%. Disparities in access to health care have improved too — as have outcomes for chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease. Costa Rica has achieved all this progress while spending less than 10% of what the U.S. spends per person on care.

“There’s both an incredible economic efficiency and effectiveness,” Bitton says of Costa Rica’s system, “and a deep humanity to it — a sense of reciprocal responsibility for every single person in the country.”

Other factors, including national investments in nutrition and sanitation programs, contributed to the country’s gains, but researchers like Bitton say that keeping nearly every single Costa Rican connected to basic primary care has helped drive significant improvements in health. Other countries, including Sri Lanka and Brazil, have borrowed from Costa Rica’s primary care playbook.

Still, it’s unclear whether Costa Rica’s model can take root in the U.S.

“The evidence is great,” says Chris Koller, president of the Milbank Memorial Fund, and coauthor of a landmark national report on how to strengthen primary care in the U.S. “The challenge,” Koller says, “is how do you graft it onto our current method of delivering and financing health care?”

Who should fund preventive care?

Funding is arguably the greatest puzzle facing the Neighborhood Nursing team. The goal is to build something akin to a public utility, serving everyone regardless of the type of health insurance they do — or don’t — have. Health insurers are the most likely to finance a program like this, which is designed to keep costs down by improving members’ health.

But getting insurers to pony up would require Neighborhood Nursing to earn buy-in from a dizzying number of entities. The residents of a single county, for example, are typically covered by as many as 50 different insurers, from Medicaid plans to private Medicare plans to employer plans. “You try to keep it simple,” says Ann Greiner, president of the Primary Care Collaborative, a nonprofit group, “But inevitably when you move toward implementing a model, you come up against this complexity.”

Insurers have collectively funded projects like statewide vaccination programs, so there is precedent for pooling resources to support all consumers, regardless of their coverage. An investment in the type of care that Neighborhood Nursing aims to deliver door to door, however, would represent a significant leap in scope.

Finding a path through an overstretched system

Health policy analysts also believe the program will likely struggle to connect patients to the country’s sprawling health and social services systems. If Neighborhood Nursing effectively opens a new, more welcoming front door to those systems, what awaits patients on the other side?

In many cases, unfortunately, that next step is into a complex maze that’s short on resources and heavy on bureaucracy. For example, Baltimore, ground zero for Neighborhood Nursing’s pilot program, leads all big cities in opioid overdose deaths, yet treatment options there are limited. Challenges to capacity plague Costa Rica’s successful primary care system, too, where patients can wait months to see specialists or get surgeries.

In the U.S., specialty care comes with additional hurdles like the need to secure approvals from a person’s insurance plan for certain procedures or medications. People needing significant social support, such as help with affordable housing, can face years-long wait lists.

“There’s no magic pill to change those structural conditions,” says Lisa Stambolis, a nurse and Neighborhood Nursing’s senior project manager. “But there are still things we can do, and we should do.”

Neighborhood Nursing has included community health workers on their teams to help people navigate these complex systems. The program is also training staff in mental-health first aid and simple techniques of cognitive behavioral therapy to make that type of basic help immediately available.

Team nurses are prepared to go the extra mile, too, to help patients like Raquel Richardson, the East Baltimore worker with high blood pressure that nurse Tiffany Riser encountered in February. Richardson initially resisted seeking care, citing past bad experiences she’d had at a local hospital. Instead of giving up, Riser switched strategies, calling a local clinic, convincing the staff to squeeze Richardson in for an urgent care visit. Nurse Riser even accompanied her patient to the doctor. “Because I had a professional with me, I felt like they took me more seriously,” Richardson says.

Early signs of community buy-in

The Neighborhood Nursing project is still in its pilot phase, building trust and gathering feedback from the community. By 2025, staff members hope to expand their services to four neighborhoods — two within Baltimore, one in the suburbs and one in a more rural area.

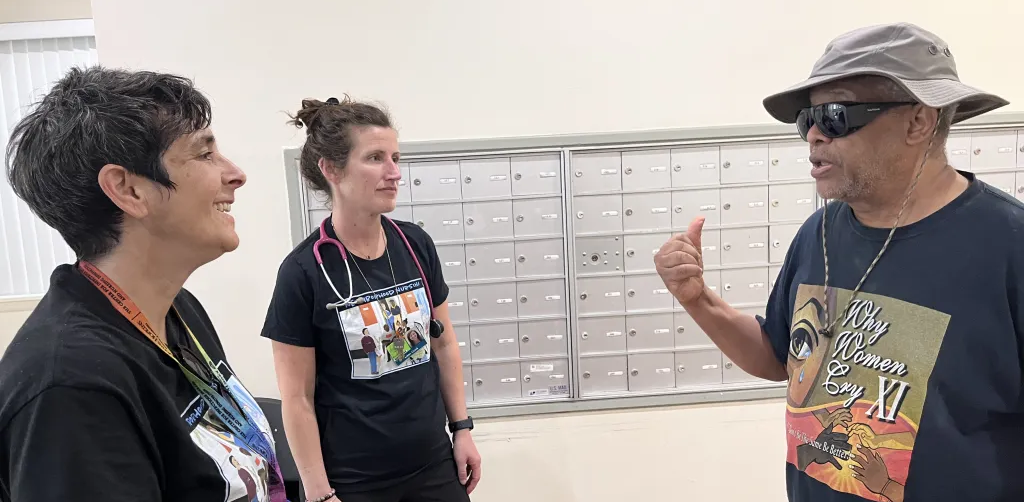

So far, the evidence the approach works is only anecdotal, but the team says they are already seeing a difference in the level of trust from community members. And a trusting connection between patient and provider is key. “The first couple weeks we showed up, it was like, ‘Who are they?’” says community health worker Terry Lindsay. “Now people are opening up the doors to their homes, saying, ‘Come on in and sit down.’”

One other sign of progress, said Sarah Szanton, is that the larger neighborhood is taking ownership and helping to shape the project.

Long-time Baltimore resident Regina Hammond and a few of her neighbors told the team they needed safer options for exercise. Together they hatched a plan to start a weekly neighborhood walking group.

“Some people walk other days too, now, as a result of meeting each other at the walking group,” Hammond says. A woman with depression joined the group and soon felt better. Another walker said he liked his neighborhood more after he discovered some new parks and an urban garden he’d never known about, despite living in the area for seven years.

The goal is to improve the health of individuals, says Szanton, and empower communities to create happier, healthier places to live.

“I think of what we’re building as like pipes in a water system,” Szanton says, “Where there’s a resource that’s flowing to every household and that connects them to each other.”

Listen to the episode:

Episode Credits

Guests:

- Dawn Alley, PhD, Head of Scale, IMPaCT Care

- Asaf Bitton, MD, MPH, Executive Director, Ariadne Labs

- Regina Hammond, Founder, Rebuild Johnston Square Neighborhood Organization

- Chris Koller, President, Milbank Memorial Fund

- Terry Lindsay, Community Health Worker, Sisters Together and Reaching, Inc. (STAR)

- Sarah Szanton, PhD, RN, FAAN, Dean, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing; Founder, Neighborhood Nursing

The Tradeoffs theme song was composed by Ty Citerman. Additional music this episode from Blue Dot Sessions and Epidemic Sound. Additional tape from Uncared For, hosted by SuChin Pak, a production by Lemonada Media in partnership with the Commonwealth Fund.

This episode was reported by Leslie Walker and Dan Gorenstein, edited for audio by Cate Cahan and for web by Deborah Franklin, and mixed by Andrew Parrella and Cedric Wilson.

Additional thanks to: Natalia Barolin, Sule Gerovich, Ann Greiner, Ashley Gresh, Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, Seiji Hayashi, Kevin Klembczyk, Kennedy McDaniel, Madeline Pesec, Tiffany Riser, Lisa Stambolis, the members of the Johnston Square Walking Group, the Tradeoffs Advisory Board, and our stellar staff!

Tradeoffs’ coverage of primary care is supported, in part, by the Commonwealth Fund.

Episode Resources

Additional Reporting and Research on Universal Primary Care:

- The Health of US Primary Care: 2024 Scorecard Report — No One Can See You Now (Milbank Memorial Fund, 2/28/2024)

- The effect of primary healthcare on mortality: Evidence from Costa Rica (Claudio Mora-García, Madeline Pesec and Andrea Prado; Journal of Health Economics; 11/8/2023)

- Primary Care in High-Income Countries: How the United States Compares (Commonwealth Fund, 3/15/2022)

- Costa Ricans Live Longer Than We Do. What’s the Secret? (Atul Gawande, New Yorker, 8/23/2021)

- What Does Community-Oriented Primary Health Care Look Like? Lessons from Costa Rica (Commonwealth Fund, 3/16/2021)

- Implementing High-Quality Primary Care (NASEM, 2021)

- Collaborative Approach To Public Goods Investments (CAPGI): Lessons Learned From A Feasibility Study (Len Nichols, et al; Health Affairs; 8/13/2020)

Note: This transcript has been created with a combination of machine ears and human eyes. There may be small differences between this document and the audio version, which is one of many reasons we encourage you to listen to the episode above!

Dan Gorenstein (DG): Hi, Dan here. For the rest of this year, we’re profiling people tackling some of health care’s toughest problems.

Sometimes, the best solutions come from the unlikeliest places, like the faraway country of Costa Rica.

That tiny country is where a group of Baltimore-based nurses found their big idea for fixing primary care in America.

Stick around to the end of this episode, which first ran last summer, for some updates.

ORIGINAL STORY:

DG: The U.S. spends more than any other high-income country on health care; yet, we have little to show for it. Life expectancy, obesity, infant mortality, you name the measure and we’re near the bottom.

Sarah Szanton (SS): People have been saying that for, what, 20, 30 years? And there hasn’t been a real solution. We need something that’s completely different.

DG: A group of nurses in Baltimore has a bold plan: Rather than treat people after they’re sick, bring preventive primary care to everybody, no matter their age, income or insurance. And deliver it right to people’s doors.

Today, inside an ambitious attempt to open a new front door to primary care in America and the barriers that could derail this dream.

From the studio at the Leonard Davis Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, I’m Dan Gorenstein. This is Tradeoffs.

*****

Nurse: Just take some deep breaths.

DG: 72-year-old Edward Murray is getting his blood pressure checked…

Nurse: It’s going to get a little tight, okay?

DG: …making sure his new dose of medication is doing its job. Michelle, a nursing student, loosens the cuff and watches the numbers.

Nurse: 130 over 86. How does that sound to you?

Edward Murray (EM): Sounds pretty good. Sounds better than 180 or something? Because it was up there. It was up there.

DG: Michelle jots down the results on a slip of paper.

Nurse: And then I’m writing down today’s date and then the time.

DG: Hands it to Edward, who plans to bring the reading to his next doctor’s visit.

EM: I’m very happy to have you all here.

DG: What’s happening here in East Baltimore on a Tuesday in late April might sound mundane, but actually, it’s radical.

SS: We’re trying to turn primary care on its head and deliver it in a completely different way.

DG: Sarah Szanton is the Dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing and the woman behind this bold initiative known as Neighborhood Nursing. It’s a partnership with three other local nursing schools: Morgan State, Coppin State and the University of Maryland.

What makes their approach unique, says Sarah, is both who it’s for and where it’s happening. It’s happening where people live. In this pilot phase, they’re in the lobbies of three apartment buildings in Johnston Square, one of Baltimore’s most marginalized neighborhoods.

And this care, it’s for everyone — sick and healthy, rich and poor, and whether they have Medicaid, Medicare, a private plan or no insurance at all.

SS: An all in approach, where everybody has access to primary care at least once a year and not just focused on the people who happen to come into a clinic.

DG: That means a nurse and a community health worker visiting with people wherever they live, checking on vital signs, medications, vaccinations, and people’s social needs — their hunger, housing, safety — keeping people healthy where they can and when they can’t, connecting them to the larger medical and social service systems.

SS: If this works, there will be fewer emergency room visits, fewer 911 calls, fewer nursing home admissions and it’ll save money because it’ll be so much more preventive.

DG: This is not what primary care looks like in America today, says Asaf Bitton.

Asaf Bitton (AB): It’s pretty much night and day.

DG: Asaf is primary care doc and director of Ariadne Labs, part of the Harvard School of Public Health. He describes what our country currently has as a sick care system.

AB: Basically we in the U.S. are okay with you having a preventable illness until and if you literally collapse in front of us. At the craziest moment, we’re going to take you into the hospital and put you in the ICU for a month and try to paste over the social ills that exist and then send you right back out to where it started and pretend that that was good health care.

DG: Compared to other wealthy countries, Asaf says, the U.S. spends much less on its primary care — about 5 cents out of every health care dollar. And we skimp on social supports like food and housing too. Take even a sliver of the money we spend on all that sick care, he says, and shift it further upstream investing it in more primary care, and Asaf believes — just like Sarah Szanton does — America could prevent a lot of suffering and inequity, and spend less money. Some of the most convincing evidence to prove that, he says, comes from Costa Rica.

Sfx: Dog barking and health care worker speaking Spanish

DG: The small Central American nation of 5 million people has pioneered a near countrywide version of Neighborhood Nursing. Teams of health workers are assigned to care for about 5,000 people in a given area, from urban cities to banana farms to remote villages reachable only by boat.

AB: Each person has access to a community health worker who sees them at least once a year in their house. It’s basically like a front door into the health system.

DG: Costa Rica developed this as a solution to lots of health care needs going unmet, especially in poor areas. Asaf has traveled to Costa Rica to study its system, and there’s one trip that always stands out.

AB: When I tell it to people in the U.S. they’re like, “That can’t be actually true.”

DG: A local care team took him to see a patient who was home after being treated for a stroke in the hospital. The patient was a poor, migrant worker from Nicaragua.

AB: I said, “So where are we going?” And they’re like, “We’ll just go wherever the iPad tells us that this person is living.”

DG: The community health worker pulled up the patient’s entire health record on their iPad, which even included how to get into the patient’s house.

AB: When you approach it, it’s down this part of the alley. Don’t go in the front door because there’s a really mean dog who will bite you. Go around the other entrance to the back door and knock three times, and then they’ll let you in.

DG: And that is exactly what happened.

AB: It was an astounding moment. Here you have a person living on the social margins who might be excluded from other societies, but in this situation, you have a sophisticated system that’s meeting her needs comprehensively and connecting her to the services that she’ll need as she recovers from a life threatening illness.

DG: Asaf explains that getting inside of people’s homes helps teams see if someone’s drinking water is clean or if they have enough to eat. It helps them adapt care to the realities of people’s actual lives.

Costa Rica’s been delivering preventive care door to door nationwide for about 30 years now. Communicable diseases like hepatitis and tuberculosis have fallen by 94 percent. They’ve cut deaths from chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease, and improved disparities too. And the country has achieved all of this while spending one-eleventh of what America spends per person on health care.

AB: It’s an incredibly efficient and effective system. And beyond that, it’s also beautifully humane. I mean, every person is counted. Every person matters. And every person is reached out to. And I find that incredible.

DG: Other countries like Sri Lanka and Brazil have taken pages out of Costa Rica’s playbook. The question that no one in the U.S. has tried to answer until now…

SS: What if we tried to do Costa Rica here?

DG: Sarah Szanton is optimistic that this idea that’s blossomed in Costa Rica can also take root in a land as different as Baltimore, Maryland, with a health care system as broken as ours.

She sees the U.S. grappling with the same core challenge that Costa Rica had: Patients struggling to get care, emergency rooms overflowing, nurses and doctors in short supply.

SS: It’s a little bit like if 10% of our houses were on fire, we would say we don’t have enough firefighters. But really what you need to do is prevent fires, which we do in general, but we’ve never done that for medical care in this country.

DG: It’s super early days, says Sarah, the Neighborhood Nursing team has only been serving a tiny corner of Baltimore for a few months now, but she’s already seeing two promising signs of progress.

First, the team is spotting what Sarah might call fire hazards and they’ve been able to snuff a bunch of them out pretty easy. Simple stuff like giving Edward Murray, the man from the lobby, a way to monitor his blood pressure when he had no cuff at home — and more serious needs, like a woman who had spent almost an entire year without a working wheelchair, risking both her health and her safety.

Terry Lindsay (TL): The brakes didn’t work on the wheelchair. One of the arm things kept falling off.

DG: Terry Lindsay is the team’s community health worker, whose job is to help address patients’ social needs. He got on the case. Terry took a trip down to the woman’s doctor’s office and politely but firmly pushed for answers.

TL: I found out that the individual’s paperwork was never submitted. So I said, “Well, is there any way you can send it?” They said, “Yeah, they’re going to get on it today.”

DG: One week later a brand new wheelchair arrived.

The second promising sign that Sarah sees is real buy-in both from individuals and the Johnston Square neighborhood.

TL: One time I saw this young guy coming through the lobby, you know, and for a lack of a better terminology, you know, he looked like a thug, right? He had his pants hanging low, all tatted up. I said, “Man, come get your blood pressure checked.” He said, “Nah.” I said, “What’re you doing right now?” He said, “I’m waiting for a friend.” I said, “Well, come on over while you’re waiting.” He came and got his blood pressure checked. Two weeks later he was back getting it checked again.

DG: Terry chalks the man’s return up to a combination of convenience, comfort and need — the same things that drew people in Costa Rica out of the shadows and into the health care system.

TL: First couple weeks we showed up, you know, it was like, “Uh, who are they?” And now it’s to the point where people say, “Are you coming back next week?” People are now opening up their doors to their homes, saying come on in and sit down and talk.

DG: Despite these signs of fertile ground, Sarah is clear that this idea she’s hoping to transplant from Costa Rica is still a very fragile seedling.

SS: There’s still so much to work out [like] how to get people’s data into the larger primary care system [and] how do we measure outcomes that matter to people and the stakeholders who are paying into this system.

DG: All details that could be dealbreakers. On top of those questions, experts say several, much larger questions loom over the fate of this project and, more broadly, the future of primary care in America. We get into those after the break.

MIDROLL

DG: Welcome back. Before the break, we heard how Neighborhood Nursing hopes to bring basic primary care to every single person’s doorstep no matter their age, income or insurance.

But despite some early signs of progress, it’s impossible to avoid asking the bigger question: Can this bold idea survive past the pilot stage? Our senior reporter Leslie Walker posed that question to 10 outside experts.

Hey Leslie, how are you?

LW: Pretty good, Dan. If I had to boil down my conversations with all these folks, across the board, they like this idea.

Montage: This is extremely innovative. // I love this. // I think it’s a great idea.

LW: But they’re also clear this is going to be a tough hill for Neighborhood Nursing to climb.

Montage: What they are trying to do is incredibly hard. // It’s really so complex. // There are lots of ways in which this can fail.

LW: Experts’ concerns come down to three big questions. But I’ve also got a couple rays of hope for you, Dan — some reasons that experts say this just might, maybe, possibly work.

DG: Excellent, I do enjoy a side of sunshine with my plate of gloom. So, let’s dive in. What’s the first cause for concern?

LW: No surprise here: Everyone’s mind went straight to money. Who’s going to pay for this whole thing? And here’s why the payment puzzle for Neighborhood Nursing is especially tough.

Dawn Alley, who spent seven years at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services trying to figure out how to fund innovations just like this, had me do this really helpful thought experiment.

I want to run it by you. Grab your abacus, Gorenstein.

DG: Wow. I do have a pen.

LW: Okay, I thought you were a little older, but a pen is fine. So, start by thinking about who Neighborhood Nursing wants to serve. A lot of health care innovations target one group, like older people or folks in heart failure. Neighborhood Nursing, they’re trying to serve literally every single person. Now for each of those people, Dan, ask yourself who’s got a financial interest in seeing that person’s health improve?

DG: In most cases, we’re talking insurers, right?

LW: Yeah, they’re the ones most likely to fund some piece of this program. Now, Dawn says, tally all those paying parties up, from Medicare and Medicaid plans to private insurers.

Dawn Alley: If you try to map this out for a county, you’re probably talking about minimum 50 different entities.

DG: 50?! 50 different insurers in every county?

LW: That’s right, each who might want to pay the Nursing team differently, use different contracts, different metrics, different incentives — define success, Dan, differently.

DG: Right, this is why these universal programs are so hard to pull off. They sound good, right? But operationalizing them means working with so many different people it’s really tough.

LW: And the main reason insurers would sign on is cause it would save them money, but retired health care executive Tom Mullen told me without any evidence so far in the U.S. Neighborhood Nursing ends up looking like a pretty risky bet.

Tom Mullen: If it doesn’t work, you’re SOL, you know.

LW: That’s shit out of luck, Dan. Money’s gone.

DG: Thanks for the translation, Leslie.

LW: Now here comes your ray of sunshine, Dan. Get those sunglasses on. Federal and state health officials are, as we speak, trying to dream up ways to incentivize more primary care innovation with an eye toward slowing down how much we spend.

One example out of several, actually, is by the end of this year, the feds will pick up to eight states for a decade-long experiment that’s going to attempt to cap how fast health care spending can grow statewide.

DG: Slow down for a second here, Leslie. You mean, across all insurers, all hospitals, cap how much their costs can rise at, let’s say, 3% a year.

LW: That’s the idea and this experiment, Dan, it’s also going to spell out what percent of all that spending has to go toward primary care.

DG: I see, so a program like Neighborhood Nursing, in theory, could be super attractive to these states because the idea behind Neighborhood Nursing, again, is more primary care improves health and can keep costs down — just the kind of thing they’re looking to do.

LW: Exactly.

DG: Okay, so that’s the payment puzzle, Leslie, that Neighborhood Nursing has to navigate. What’s the next big question your experts had?

LW: Next one: Can these teams of nurses and community health workers effectively connect folks to all of the other health and social supports they’re probably going to need?

Chris Koller: They are delivering care, but they’re not delivering the full suite and so they have to be part of something bigger.

LW: Chris Koller is the president of the health care philanthropy the Milbank Memorial Fund and a coauthor of a landmark national report about how to fix primary care in America.

And his point, Dan, is that as these teams get inside people’s homes they’re going to uncover needs for everything from specialists and medications to food stamps and mold removal.

DG: Yeah, these teams effectively are opening up a new front door to our larger health and social services system and the question is: What’s waiting for them on the other side?

LW: Yeah, and there’s real reason to worry that nice looking new door might lead to some pretty frustrating dead ends. For example, Neighborhood Nursing might not care what insurance people have, but doctors do.

DG: Because the doctors get paid by those insurance companies. And I know finding those docs is a big part of the challenge. When I was in Baltimore talking with people everybody agreed that there’s this huge need for mental health and addiction services but not enough providers to meet that demand.

LW: And those kinds of capacity constraints you’re talking about there, Dan, are another reason experts are concerned about where this front door is going to lead. That’s a weakness in Costa Rica’s system, too, where people wait months to see specialists or get surgeries.

DG: I still have my sunglasses in my pocket. Is there any reason for optimism here, Leslie, before we move to the last big question on your list?

LW: I would not pull them fully on. But I will say, if anyone’s proven good at navigating our confusing, overstretched systems of care in this country, it’s community health workers like Terry from the first half who Neighborhood Nursing has got on the case. But there’s no sugarcoating the fact that some folks are very likely just not going to be able to get what they need.

DG: Okay, so what’s the third and final question?

LW: I’ll keep this one short: Can this program scale beyond Baltimore? It’s a question Sarah Szanton’s thinking about a lot.

DG: And why is that?

LW: About 15 years ago she launched this other program designed to tweak older people’s homes, like adding handrails, making showers safer, so folks could stay instead of moving into nursing homes. Multiple trials showed the program improves people’s health and saves, actually, a ton of money. But even though it’s been around for more than a decade and expanded to more than 20 states, it’s only served about 10,000 people.

DG: So why does Sarah think this time will work?

LW: Well, she said she’s going straight to the money and the power.

SS: Who needs to buy into this to want to scale it, and what do they need to make that happen?

LW: In other words, she’s going to insurers, policymakers, some hospitals, trying to get them on board early. And so far, she says she’s getting a warm reception.

DG: Alright, so you’ve given us some reasons for both a lot of caution and a hint of optimism. There’s one more break in the clouds though that I wanted to share with you, Leslie, based on my time I spent in Baltimore back in April.

LW: A sunshine surprise! Love it.

Regina Hammond (RH): We’re actually walking down the street at the moment if you want to take a walk around the neighborhood.

DG: That afternoon, Regina Hammond, a longtime resident of Johnston Square, invited me on this walking group. Now, they got some help organizing it from Sarah’s team but it was spearheaded by Regina and some of her neighbors.

RH: Some other people in the neighborhood they walk other days too, now, as a result of meeting each other at the walking group.

DG: The reason there’s some sunshine here, Leslie, is that both these folks and the Neighborhood Nursing team told me having the program around is kind of putting being healthy more on the map. For example, a woman with depression joined the group, helping her feel a bit better. A man discovered there’s an urban garden a few blocks away after he did one of the walks, and that made him feel better about where he lived.

And to me this was a sign, a small one for sure, but a sign that at least a handful of people are taking a program started by these nurses, inspired by a country 2,000 miles away, and starting to make it their own.

LW: And I’m so glad you brought this up, Dan, because that’s part of Sarah’s ultimate vision here too. She’s not only trying to improve the health of individuals but also empower communities to create happier, healthier places to live — whatever that means to them.

SS: Health is different for everybody, and health isn’t just being free from suffering — it’s also experiencing joy and being able to participate meaningfully in society. And if people have their social needs met and their medical needs met, they’ll be able to do that.

DG: Leslie Walker, a pleasure working on this story with you.

LW: Likewise, Dan.

UPDATE:

DG: Since this episode first aired in the summer of 2024, Neighborhood Nursing has branched out to three more Baltimore neighborhoods, with plans to head to Maryland’s more rural Eastern Shore next.

They’re also adding services, like nurses to treat pain and addiction. And, they’re meeting people in new places like libraries and churches.

Back in Johnston Square, where this whole thing started, Regina Hammond’s walking club is still making the rounds.

I’m Dan Gorenstein. This is Tradeoffs.

(click + to read full transcript)