A story by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi)

Photos by Brent Stirton/Getty Images for DNDi

June 2024, Dubreka, Guinea: A snap rainstorm is pouring down on the corrugated tin roofs of the sleeping sickness hospital in Dubreka, Guinea, and temporary rapids are flowing through the front gate into the open-air complex. It is the rainy season in this city just north of Guinea’s capital, Conakry.

As nurses and doctors take cover, a woman runs through the gate. She deftly hops over the massive puddles, shielding her head with her plastic-wrapped medical records, and runs into a room where health workers are waiting out the storm.

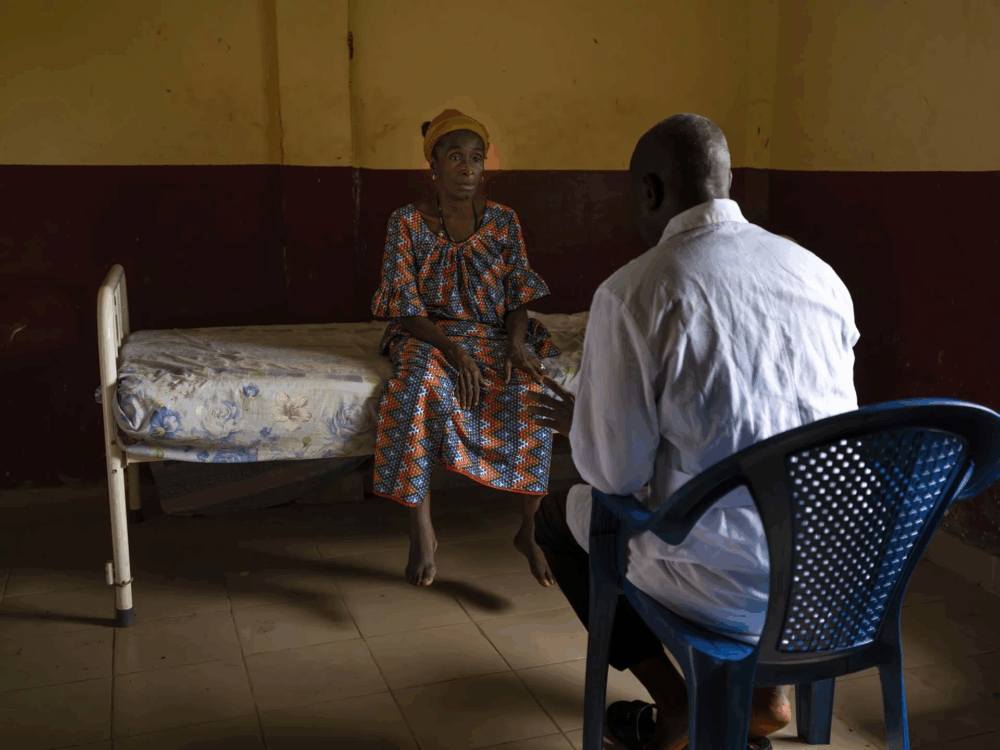

Her name is Macire Sylla. She has been suffering for some time now. The rain pounds on the tin roof, creating a deafening roar as she explains her struggle of the past year.

Macire lives in Tobolon, not far away. A year ago, a team from the hospital came to her neighbourhood to test people for human African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness – a nightmarish neglected tropical disease spread by the bite of tsetse flies that live in the mangroves that surround Dubreka and most of the Guinean coast.

Everyone in the village was given a rapid diagnostic test, and Macire initially tested positive for sleeping sickness; but when she was given a confirmatory test, it was negative. So she didn’t receive treatment at that time.

Over the course of the year, Macire began to feel worse – pain and aches, weakness, and extreme fatigue. She started to suspect that maybe she did have the disease after all. She knew from the hospital team that without treatment, most patients with sleeping sickness eventually die.

And that is how she ended up today at the ‘Trypano Centre’ in Dubreka. (Trypano is short for human African trypanosomiasis, the scientific name of sleeping sickness.)

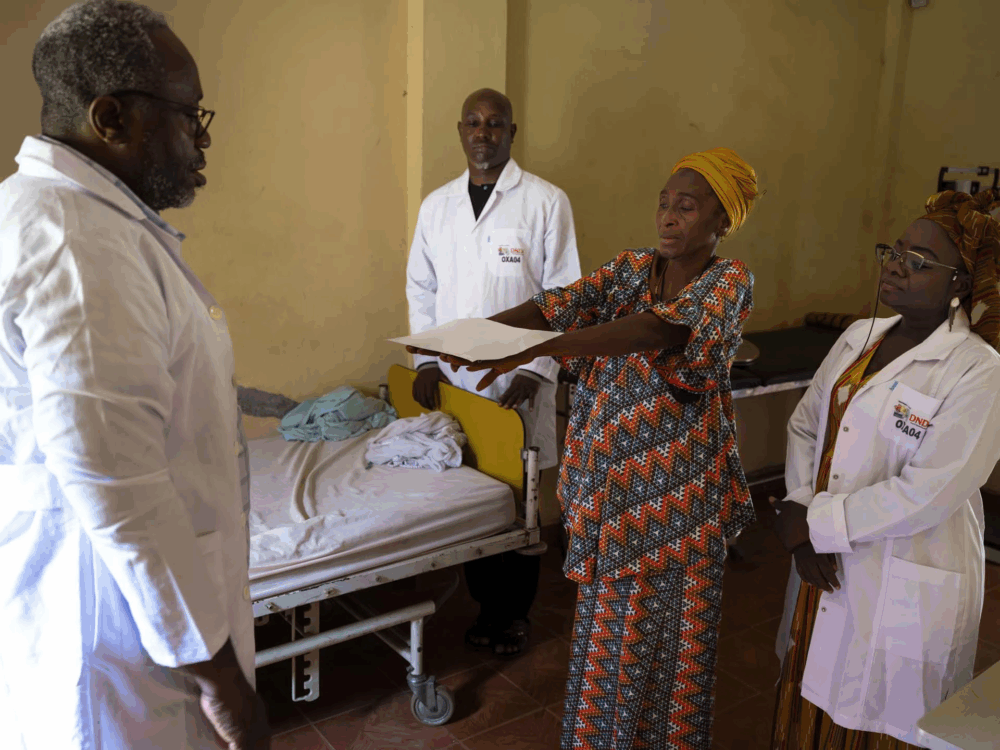

As the rain abates, her blood was taken at the Trypano Centre’s laboratory, and while her results were being analysed, a team carried out simple clinical exams, to look for the neurological symptoms of sleeping sickness – one of the many unique features of this parasitic disease.

While the symptoms of the first stage of sleeping sickness can resemble malaria, with fever and pain, the parasite later invades the central nervous system. At this point, people develop neuropsychiatric symptoms such as sleep disruption, confusion, lethargy, aggression, and convulsions.

To test for these neurological signs of sleeping sickness, the team has Macire conduct a set of simple exercises: reach her hands out, hold a paper on the top of her hands, touch her nose. People with sleeping sickness often can’t pass these simple physical tests, but Macire is able to do almost everything. Perhaps she doesn’t have the disease after all.

Across the hospital grounds in the laboratory annex, Oumou Camara, the Diagnostic Manager at the National Programme for Neglected Tropical Diseases, sees a different story under a microscope. Despite having tested negative a year ago, today Macire’s blood sample was full of the Trypanosoma brucei gambiense parasites that cause sleeping sickness.

She was positive for sleeping sickness.

Next to Oumou, French researcher Dr Bruno Bucheton from the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD – from the French Institut de Recherche pour le Développement), is nevertheless elated. Dr Bucheton, who has been in Guinea for 15 years working on sleeping sickness, sees the bright side.

‘This is great news – if this lady hadn’t returned, she might not have been diagnosed,’ said Dr Bucheton. ‘The disease would have continued to progress into a later stage, and if she was bitten by a tsetse fly, she should could have passed on the disease to someone else. Now we will be able to cure her. She will feel better – and her life will be saved.’

Macire is one of a rapidly dwindling number of sleeping sickness cases in the country because Guinea is on the cusp of eliminating the disease.

On 30 January 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) validated Guinea as having eliminated the disease as a public health problem, meaning the country now counts less than 1 case for every 10,000 people.

This is the first disease that the country can claim to have eliminated and a major milestone in the Africa-wide campaign to eliminate sleeping sickness. Historically, Guinea was the country most affected by sleeping sickness in West Africa, reporting a large number of cases of the gambiense strain of the disease, alongside the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), South Sudan, Angola, and Chad.

The National Sleeping Sickness Programme in Guinea and its national and international partners have used all the tools at their disposal to achieve this milestone – from the small ‘tiny traps’ that dot the mangrove coasts of Guinea to rapid diagnostic tests that allow the Programme to quickly identify patients.

Innovative research has been a hallmark of this successful elimination programme. Guinea was also a partner country for clinical trials led by the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) to develop innovative new treatments for sleeping sickness. This includes acoziborole – the one-dose cure that could be the key to eliminating the disease for good.

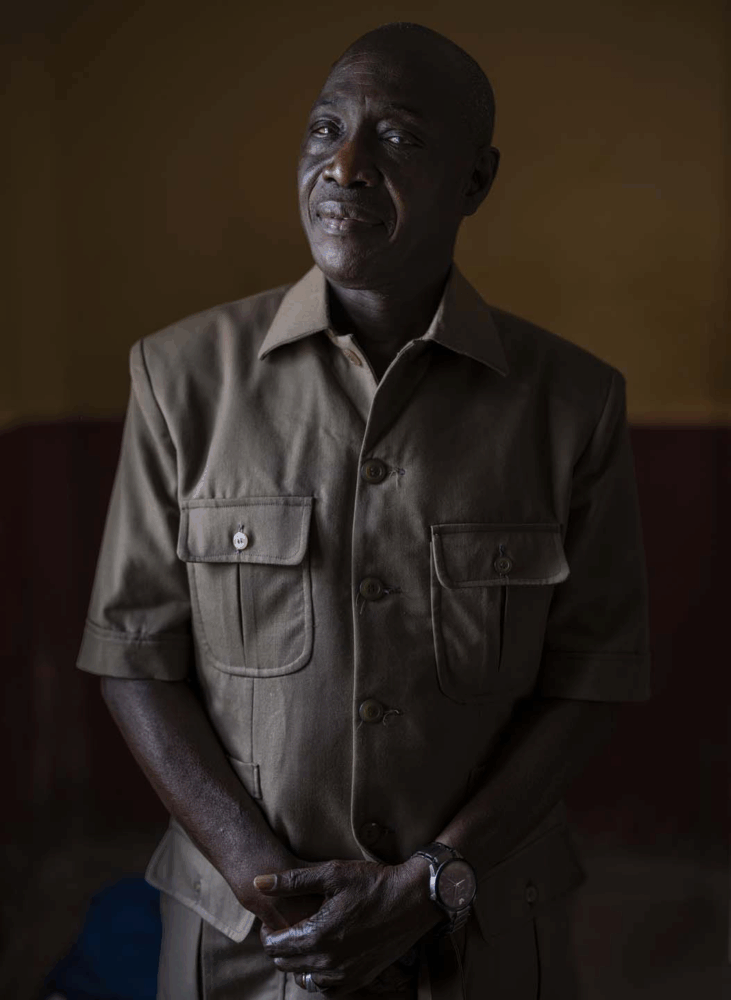

‘It’s the team that wins,’ said Professor Mamadou Camara, National Coordinator on Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) in Guinea, who has dedicated most of his career to tackling sleeping sickness. He helped set up Guinea’s National Sleeping Sickness Programme in 2002 and has since created international research collaborations with 14 organizations around the world and in Africa.

“We have been able to achieve this thanks to research, innovation, and human perseverance. It’s the international community that wins. It’s the international community that is winning against a disease.”

— Prof. Mamadou Camara, National Coordinator on NTDs, Guinea

How did Guinea reach this milestone? And importantly, how can Guinea take the next step and finally eliminate the disease for good?

Coming soon! Step 1: A Unique Foe – Controlling the Tsetse Fly

Watch this video to learn more about this successful program by DNDi:

In January 2025 Guinea announced that it had eliminated sleeping sickness as a public health problem. This is the first disease that the country can claim to have eliminated and a major milestone in the Africa-wide campaign to eliminate sleeping sickness.

The National Sleeping Sickness Programme in Guinea and its international partners – among them the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD), the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), and the Institute Pasteur – have used all the tools at their disposal to achieve this milestone: small ‘tiny traps’ that dot the mangrove coasts of Guinea, rapid diagnostic tests, and revolutionary new medicines that are changing how doctors treat their patients.

Related Articles

Bölët Mouna: Inside Guinea’s Quest to Eliminate Sleeping Sickness (Step 4)

Guinea has achieved a historic milestone by eliminating sleeping sickness as a public health problem, becoming the first country to conquer this deadly neglected tropical disease with the support of DNDi. In Step 4, read about going the last mile.

Bölët Mouna: Inside Guinea’s Quest to Eliminate Sleeping Sickness (Step 3)

Guinea has achieved a historic milestone by eliminating sleeping sickness as a public health problem, becoming the first country to conquer this deadly neglected tropical disease with the support of DNDi. In Step 3, read how going door to door helped the process.

Bölët Mouna: Inside Guinea’s Quest to Eliminate Sleeping Sickness (Step 2)

Guinea has achieved a historic milestone by eliminating sleeping sickness as a public health problem, becoming the first country to conquer this deadly neglected tropical disease with the support of DNDi. In Step 2, read how community trust was built.