For Morie Abibu, a 56-year-old father paralyzed from the neck down, each breath had become a struggle. A tumor growing at the base of his skull pressed against his spinal cord, slowly suffocating him. Just months earlier, his condition would have been a death sentence in Sierra Leone, a country of eight million people without a single neurosurgeon.

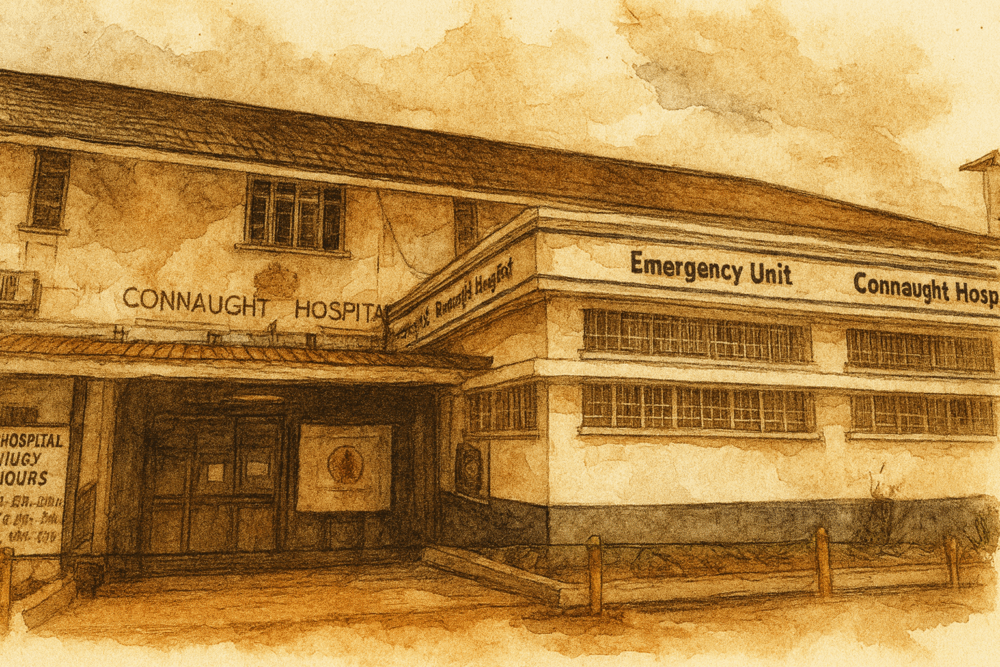

But in early 2025, Abibu found himself under the care of Dr. Alieu Kamara, Sierra Leone’s first and only neurosurgeon, at Connaught Hospital in Freetown. What followed was not just a medical procedure, but the culmination of years of international collaboration and local determination to bring neurosurgical care to one of the world’s most underserved regions.

From Factory Worker to Pioneering Surgeon

Dr. Kamara’s path to neurosurgery began in childhood during Sierra Leone’s brutal 11-year civil war. Born in a small eastern village, he spent years hiding in the bushes with his family to escape rebel attacks. A soccer accident in secondary school, where he accidentally broke a friend’s arm, sparked his resolve to become a doctor.

Without funds for medical school tuition, Kamara worked for two years in a plastic manufacturing factory. A scholarship eventually brought him to Jilin, China, where he spent 12 years earning both an MD and Ph.D. in orthopedic surgery before returning home in 2020.

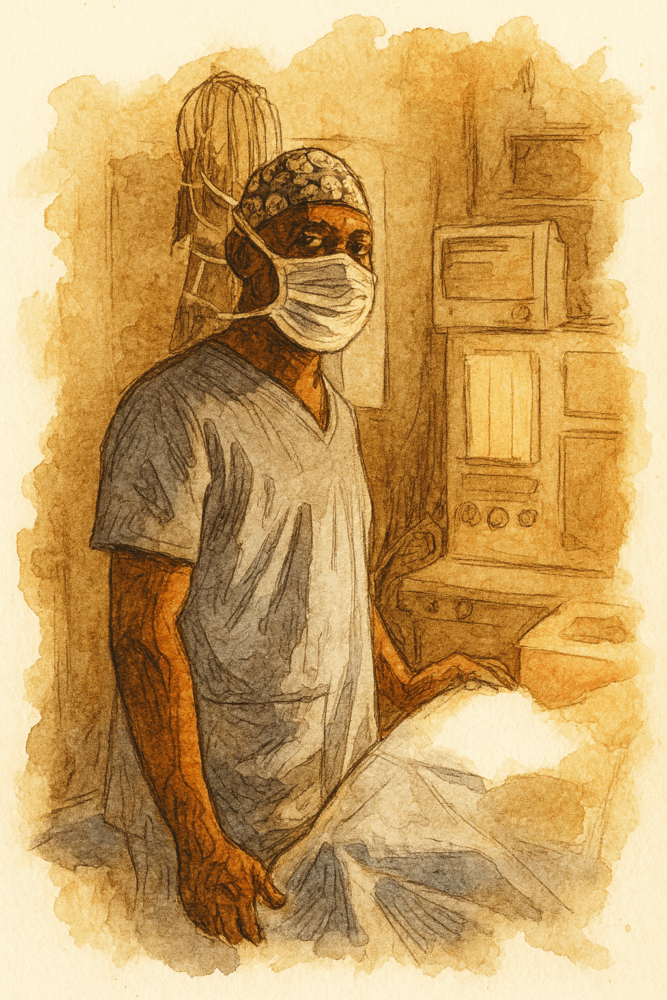

Back at Connaught Hospital, Kamara treated fractures and broken bones, but watched helplessly as patients with head and spinal injuries died from conditions he knew could be treated. “We used to lose a lot of patients due to head injuries, spinal cord injuries, spine fractures and the like,” he said in an article by Goats and Soda for NPR. “There was nothing we could do for them.”

The need was clear: Sierra Leone required a neurosurgeon, and Kamara was determined to become the first.

Building a Network of Hope

The transformation of Sierra Leone’s neurosurgical landscape required more than one person’s ambition. It demanded an international network of advocates, each driven by personal connections to the country’s medical needs.

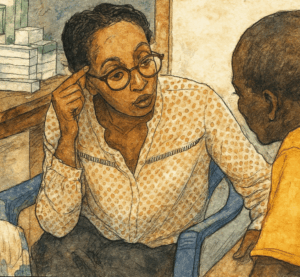

In 2021, Dr. Fatu Conteh, a neurosurgery resident in California who had fled Sierra Leone during the civil war, returned home for a visit. When her grandmother suffered a stroke and became paralyzed due to lack of timely treatment, Conteh was devastated but determined. She connected with Dr. Sonia Spencer, chairperson of the University of Sierra Leone Teaching Hospital Complex, who challenged her to “go find us some partners.”

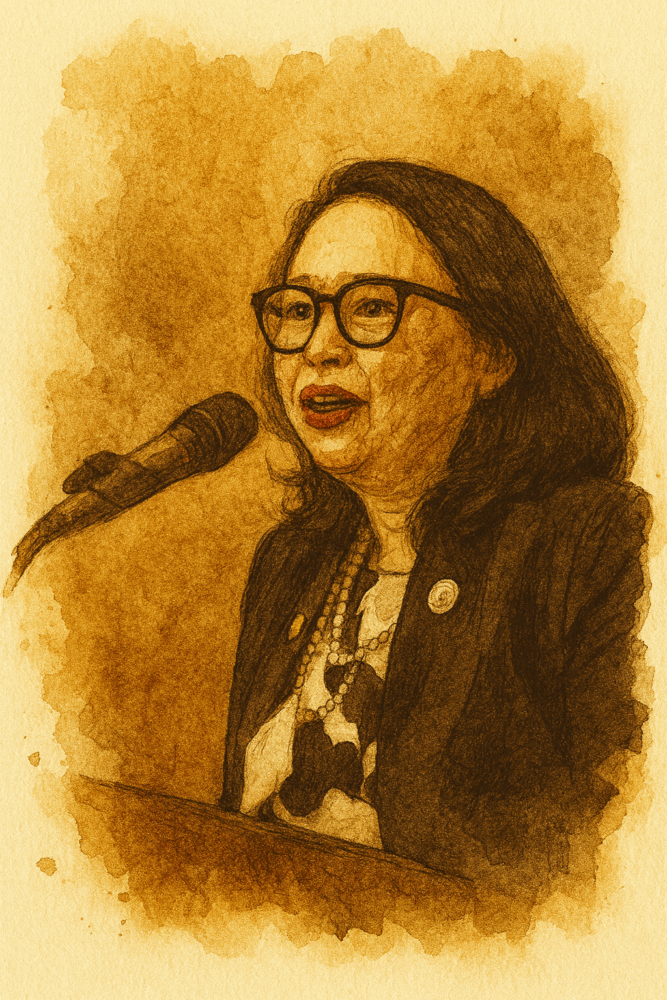

What followed was a methodical campaign of cold emails, Zoom calls, and persistent networking. Progress remained slow until Conteh met Dr. Kee Park, co-chair of the Global Neurosurgery Committee, whose international connections proved invaluable. Park’s most significant introduction was to April Sabangan, CEO of Mission Brain.

Mission Brain is a California-based nonprofit dedicated to expanding access to neurosurgical access worldwide through innovative training programs and global partnerships. Founded in 2010, the organization has supported over 1000 neurosurgical procedures and established chapters across multiple countries, including placing the first neurosurgeon in South Sudan.

After visiting Sierra Leone in 2023, Sabangan committed to the organization’s largest capacity-building project yet, focusing on creating sustainable frameworks that enable long-term neurosurgical care rather than temporary intervention. Mission Brain would arrange Kamara’s specialized training and provide essential infrastructure, from surgical supplies to nursing education.

The funding came from personal donations, foundation support, and creative fundraising—including Conteh asking for donations to the project instead of wedding gifts. Dr. Abdessamad El Ouahabi, a Moroccan neurosurgeon, offered free 18-month neurotrauma fellowship training. Surgical instruments traveled from Pakistan to Geneva, then aboard Mercy Ships to Sierra Leone.

Surgery in the Dark

When Kamara finally operated on Abibu in 2025, the challenges of practicing medicine in a resource-limited setting became starkly apparent. The operating room required improvised equipment: surgical gowns rolled and taped into bolsters, burned-out ceiling bulbs replaced by ladder, flies swatted away with electric swatters.

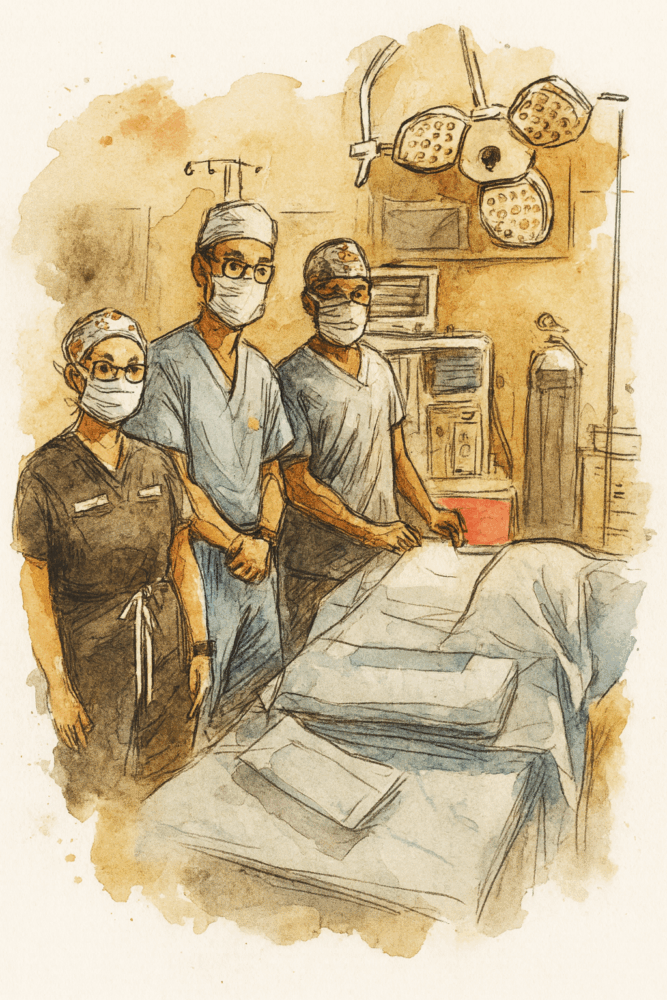

As Kamara made his first incision, assisted by visiting Stanford surgeons Dr. Seunggu Han and Dr. Silvia Vaca, the delicate work of removing the tumor began. An hour and a half later, he extracted a chunk of diseased bone, exposing the pale spinal cord beneath.

Then the lights went out. Power outages during Sierra Leone’s rainy season are common, but this one came at the worst possible moment. With Abibu’s spine exposed, the operation couldn’t stop. Battery-powered surgical headlights provided the only illumination as Kamara continued working in near darkness, controlling bleeding and smoothing bone edges. The power failed twice more during the three-hour procedure.

When Kamara finished stapling the incision closed, everyone exhaled collectively. They had completed Sierra Leone’s first spine surgery.

Small Movements, Great Hope

Six hours later, the real measure of success came not from medical textbooks but from Abibu’s toes. After months of complete paralysis, the subtle movement of his left foot—described by Dr. Vaca as “like the beat of a butterfly wing”—represented something approaching a miracle.

The surgery’s success extended beyond one patient. Within the program’s first few months, other lives were transformed: a tailor who had lost all sensation in his limbs regained feeling in his legs; a young man who fell from a palm tree while harvesting oil avoided permanent paralysis; a family member of a medical colleague walked out of the hospital pain-free.

Each case cost approximately $300—half an average family’s yearly income in Sierra Leone, but a fraction of what similar procedures cost elsewhere.

Challenges and Sustainability

The program faces significant ongoing challenges. Connaught Hospital’s limited supplies mean patients risk surviving surgery only to succumb to infection from inadequate wound care. The hospital’s single CT scanner, located at a distant military facility, makes monitoring recovery difficult over bumpy roads.

Many patients struggle to afford even the modest surgical fees, forcing families to borrow money or go without treatment. Abibu’s family borrowed their surgical costs from a neighbor—a common arrangement that highlights the economic barriers to care.

Yet systemic improvements are underway. The government is developing a dedicated neurosurgery ward and has purchased a CT scanner for Connaught Hospital. Twenty-four nurses have received neurotrauma certification through Mission Brain’s support. A “Sababu fund”—named after the local Creole word for kindness—will help cover costs for indigent patients.

A Ripple Effect

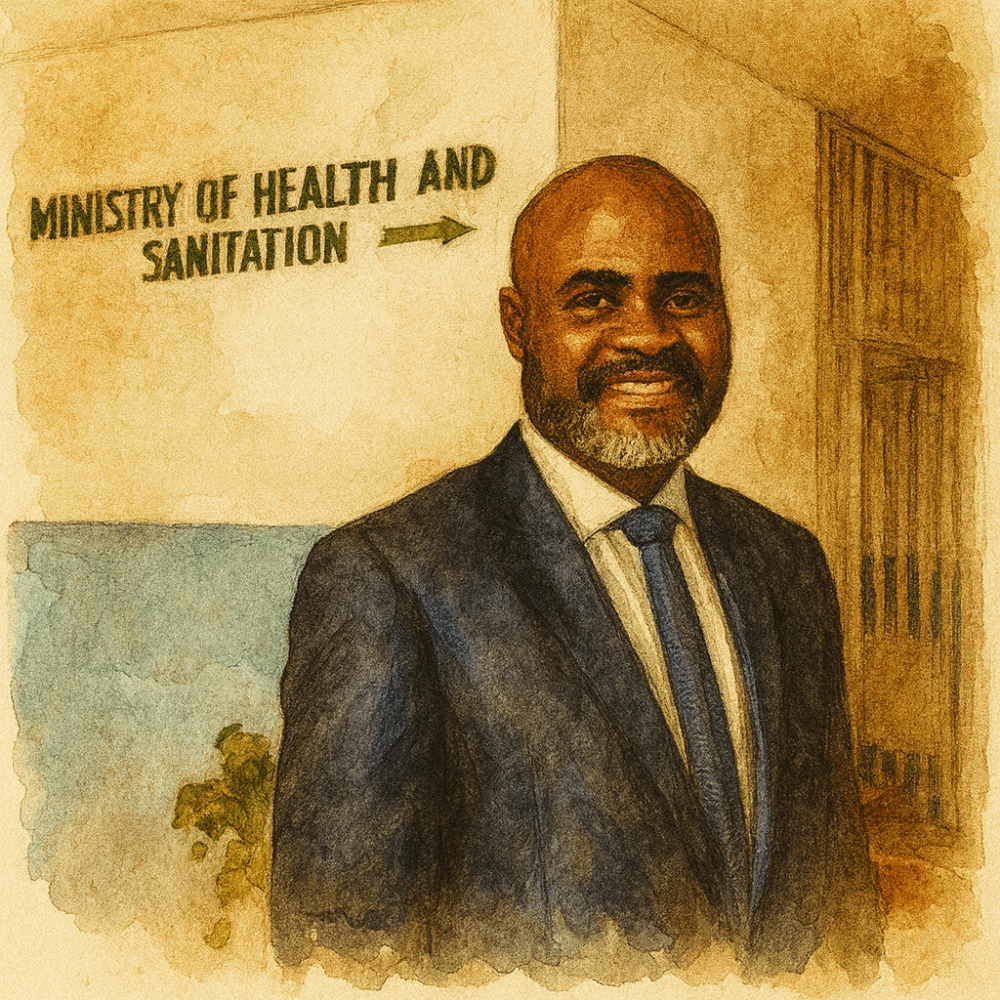

For Dr. Mustapha Kabba, Sierra Leone’s deputy chief medical officer, the neurosurgery program represents proof of what’s possible in the country’s health sector. “I see this as a litmus test,” he said in the interview with Goats and Soda.

Kamara has begun training the next generation, with medical students and residents rotating through his surgeries. He gives all patients his phone number and takes calls at any hour. “I work around the clock. I work 7 days a week. I have to follow up on patients,” he said in the interview with Goats and Soda.

The ultimate goal, Kamara emphasizes, is self-sufficiency. The international support that made his training possible was never meant to create dependence, but to build local capacity that can grow and eventually stand alone.

For now, however, the work continues one patient at a time. In a country where neurosurgical conditions once meant certain death or permanent disability, the simple movement of toes represents not just medical success, but the restoration of hope itself.

Watch this video to learn more about Mission Brain and “Dr. Q”:

This summary is based on the following articles:

- One neurosurgeon, 8 million patients, by Sophia Li for Goats and Soda, NPR

- Sierra Leone’s First Neurosurgeries: Made Possible through Local Collaboration, by Mission Brain

Related Articles

Last Mile Health: Bringing Healthcare to the Most Remote Communities

Last Mile Health transforms healthcare delivery in remote communities by training and paying local health workers, ensuring no patient is out of reach in Liberia, Ethiopia, Malawi, and Sierra Leone.

Partners In Health Expands Community-Based Mental Health Care Across Six Countries

Six mental health program leaders at Partners In Health pioneer community-based care across Haiti, Peru, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Rwanda, and Mexico. They transform stigmatized, inaccessible treatment into integrated primary health services.

Transforming Maternal Health Care in Sierra Leone: Partners in Health’s Comprehensive Approach

Partners In Health works alongside Sierra Leone’s Ministry of Health to improve maternal health outcomes through innovative programs, cultural integration, and modern facility development, addressing one of the world’s previously highest maternal mortality rates.

awesome

Good afternoon, am just wondering if you guys are providing treatment for someone with Spinal cord injury. I will need urgent medical attention for my relative in Sierra Leone

Please get in touch directly with Connaught Hospital in Freetown.