William H. Foege, the epidemiologist whose innovative containment approach proved essential to eradicating smallpox, died on January 24, 2026, at his home in Atlanta. He was 89. The cause was congestive heart failure.

Smallpox had killed an estimated 500 million people throughout history. Those infected developed sores of oozing pus and blood; Foege said he could smell the disease the moment he entered a room. Working as a Lutheran missionary doctor in eastern Nigeria in 1966, he faced an outbreak but lacked sufficient vaccine to inoculate everyone in the region. Out of necessity, he devised a more surgical approach: his team identified infected individuals, isolated them, vaccinated their contacts, then vaccinated the contacts of those contacts, and finally vaccinated people gathered in public places like markets.

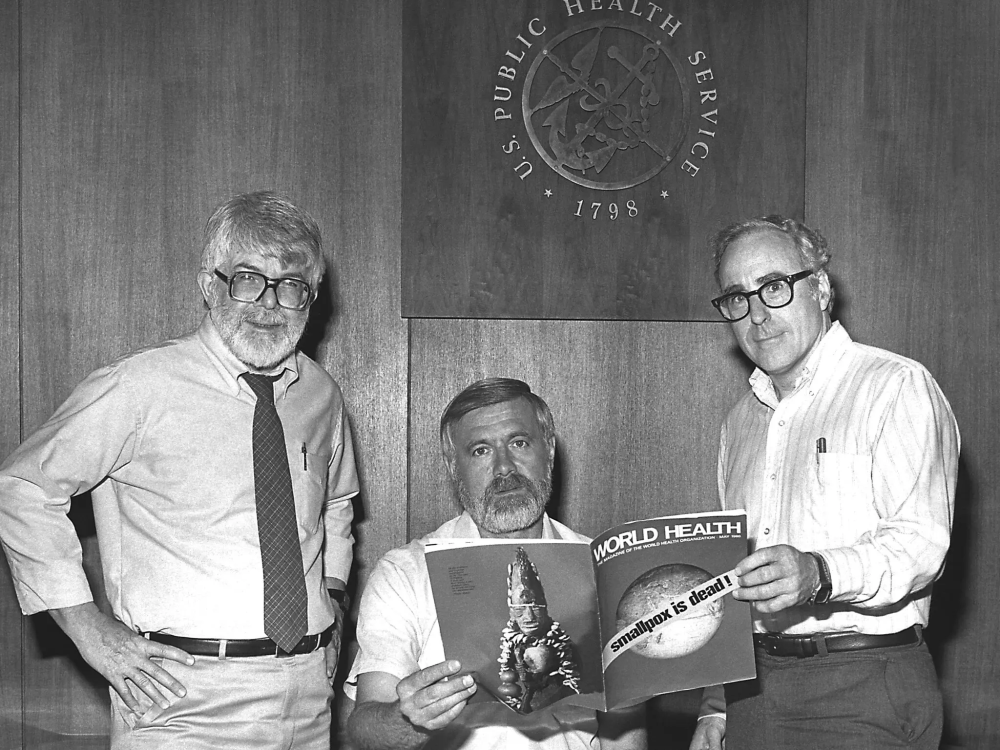

Foege later explained his method drew on experience fighting wildfires in the American West as a young man. Fire crews extinguished the blaze’s heart while preventing its spread by clearing perimeters down to bare soil. The approach, now called ring vaccination, became the foundation for global eradication efforts. The last naturally occurring case appeared in Somalia in 1977; three years later, the World Health Organization declared smallpox eliminated—the first infectious disease ever eradicated.

During Nigeria’s civil war, Foege remained behind after his family was evacuated. When federal officials in Lagos cut off vaccine supplies to the eastern region, he drove 350 miles and raided a government warehouse, loading his truck with stolen supplies while a colleague distracted a security guard. Encountering rebel roadblocks on the return trip, he talked his way through by explaining he had just stolen from the federal government.

As director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 1977 to 1983, Foege expanded the agency’s focus beyond infectious disease to include auto injuries and gun violence. After leaving government, he led the Task Force for Child Survival (now the Task Force for Global Health), which helped increase global childhood vaccination rates from roughly 15 percent to 80 percent by 1990. He also served as executive director of the Carter Center from 1986 to 1992.

Former CDC director Thomas Frieden called him “the Babe Ruth of public health.”

Foege often spoke of the moral obligation to be what he called a “good ancestor.” In a 2016 commencement address at Emory University, he told graduates that the measure of civilization comes down to a single question: how people treat each other. “Kindness is the basic ingredient,” he said, quoting both his brother’s advice to his nephew and President Carter’s favorite Bible verse. He urged the audience to seek equity and justice, and closed with a line from the novel “Cutting for Stone” that he hoped would stay with them: “Home is not where you are from. Home is where you are needed.”

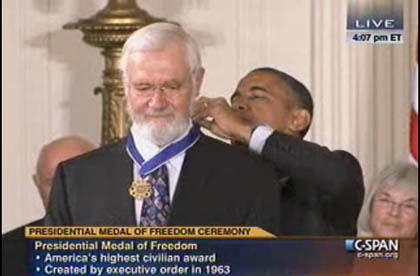

President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012. His survivors include his wife Paula, two sons, and four grandchildren.

This summary is based on the following articles:

- William H. Foege, Key Figure in the Eradication of Smallpox, Dies at 89, by Keith Schneider and Sheryl Gay Stolberg for the New York Times

- Commencement speaker William Foege’s ‘Lessons I am Still Desperately Trying to Learn,’ from Emory University

- William Foege, from Wikipedia